YOUR VOICE IN MY HEAD (AND MINE IN YOURS)

Danni Zuvela and Joel Stern (April 2017)

We Are We, Uttering Together

Polyphony is a state in which we hear many different voices, in their full texture, simultaneously. (Poly/many + phonos/voices). Musically, it is different to harmony, which is a system for organising pitch relationships. Polyphony in music refers to a texture containing many independent melodies or voices within a given framework as practised throughout the world. Polyphony needn’t, but can still “have harmony”.

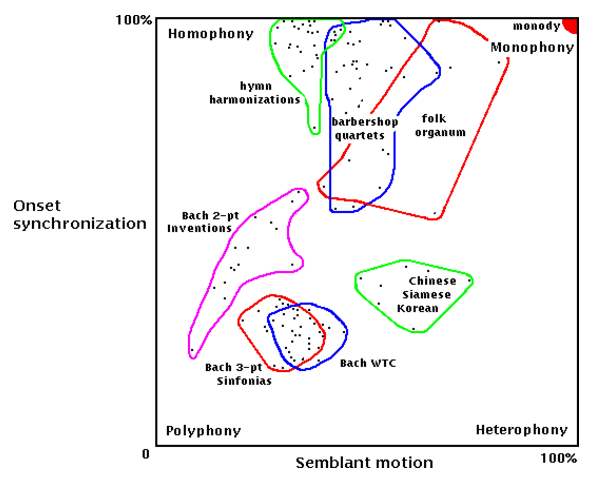

Figure 1. Useful because it is so unuseful

Socially, polyphony refers to the dynamics of collective voicing. When many sounds come together as one, we say they are in unison. The problem with unison is that it means ‘one sound’, which we know can never truly exist – it’s more a guideline, an aspiration, a reference point, a melody to follow, than it is an actual state to achieve.

—We are as close as can be, we are totally in harmony, on song, as one (point)

—We will remain irreducibly separated, because we will always be, in the first and last instance, separate voices (counterpoint).

It is in the trying for togetherness, in reaching out for each other, that we must acknowledge the discontinuity between us, because that void is also the space of difference where frictions and dissonances resound.

Your Head in My Voice

There is no dissonant sound per se. Joseph Jordania reminds us that dissonance is a quality of an interval that shouldn’t be there – because “in the moral economy of sounds, dissonance signifies evil (Devil).” (Which is why classical pieces end on a proverbial high note – good-God must be heard to triumph). Joseph hears polyphony ethically and evolutionarily, as a tactic mobilising dissonances for the voice under siege. When a pack howls, it’s polyphonic. In deviant harmony, the vocalic body multiplies the pack’s sounding: more populous, more many, more difficult to attack. Threatening violence against the stranger, polyphonic dissonance, in the wild, correlates with survival.

For Bakhtin, our utterances are always polyphonic (many-voiced) and heteroglot (other-languaged). When we speak, our voice is not solely our own but rather is inflected with the accumulated weight and tone and colour and expectations of our history, our social position, our sum of experiences, our place in the world now and where we dream to be. We are always speaking other languages, in many voices, all at once – this, perversely, is what constitutes us as individuals. As individuals, we are loaded with polyphonic vocabularies: “(e)ach word tastes of the context and contexts in which it has lived its socially charged life; all words and forms are populated by intentions.” I can embody your utterance even while saying it in my voice. As in quotation, or mimicry, or ventriloquism, you don’t actually have to be present for this to be dialogue.

Polyphony is my utterance that consumes yours; it is your voice in my head (and mine in yours).

Bad Communality

If polyphony is the many voices in the one voice, it is also the voice in disguises. A plural-singular can be many and one; it is both. (Everybody solos, nobody solos). When we raise our voices together, the voice-body we conceive is a noisy soul. The question concerns the ethic of listening amidst collective voicing, since the promise of communion comes bundled with the prospect of individual dissolution into the greater group-body.

So we are all singing from the same songsheet – Think about crowds, choirs; think about speaking in tongues. Aren’t they all the state of being possessed by the voice of another – a voice that speaks through you – if somewhat unintelligibly – from a power that’s beyond you? Aren’t they all, to some degree, requisitions?

Aren’t they humans, instrumentalised?

Steven Connor says the collective voice of the choir is essentially fantastic:

There is in fact no vox populi that is capable of sounding upon the ear, however irresistibly it may seem to claim the condition of voice and clamour for hearing in the urgent yet hallucinatory voice-body of chorality. Chorality is the means whereby we allow ourselves the collective hallucination of collectivity. The point of trying to understand the power we allow ourselves to exercise over ourselves in the fantasies of chorality is to be able to refuse and as necessary rescind its demands.

The throat thickens, the sign solidifies and our ears rush with blood, so we don’t notice or maybe don’t care about the modulations of the meaning, because we are uttering together.

References

Mikhail Bakhtin, Problems of Dostoevsky’s Poetics

Steven Connor, Choralities