Field Notes from the Giant Cuttlefish Aggregation 2019

The First Unsaying

To open the ears, we sometimes proceed from silence, as in listening walks, vipassana meditation, and vigils. Being together without speaking together changes us. Respectful group silence is necessary, it is felt, so that we can really hear our environment, and by extension, ourselves within it: unshaped by speech, attention may be re-tuned, heightened, intensified, opening the space in which thoughts and questions may bloom.

On reflection, there were some notable moments of group quiet on our week-long Artist Camp to Point Lowly, South Australia, the site of the world’s only known gathering of the giant Australian cuttlefish (Sepia Apama). For starters, there were times when we literally couldn’t hear anything. To witness the cuttlefish aggregation, we donned an increasingly tight series of ocean skins - inner liner, 3/2mm wetsuits and sleeveless hooded vest. The latter’s ear-covering function served, we discovered, to keep out not just wind (and water), but also most sound.

It wasn’t a complete silencing; floating in that other world, what we experienced was more of a muffling, a backgrounding, an underplaying of sound in its preferred medium of water. In that swaddled space, certain sounds were still recognisable, sometimes surprisingly so - friends’ exclamations, the hiss of a passing scuba diver, the electro-static of crackling krill fields. And there is also the matter of proper snorkel technique - a one-word language for clearing the pipe of water, which involves pursing the lips and forcefully expressing the word ‘Two!’ You’re kind of spitting air, which is what you do when you talk of course, but with snorkelling, it’s more vehement, explosive, because it has to be, to expel the seawater from the breathing tube in a blast. The need for air makes it a language learned under some duress. (In the water, human lips and lungs and brains need to be recruited and retrained quickly, for our survival, because they are not gills or blowholes). Above the waterline, we made a windswept chorus of splutters, burbles and hooting ‘two’s. But, in the water, mostly, it was quiet.

This ability to selectively deafen ourselves - even as a wetsuit side-effect - raises the inescapable politic of ocean listening. We sight-dependent land-creatures are unaccustomed to and generally uninterested in listening underwater – unless it’s for military exercises or seismic exploration industries. These exceptions are fairly telling: these eavesdroppers silence others with explosives. There, in the water, one of our most important acts of listening took place, as a collective of temporary amphibians in the process of realising how imperfectly we were hearing, and chilled by more than the water temperature. We were in their space, the place where anthropogenic sound travels, swift and brutal. The noise our species makes with underwater exploration, weapons testing and shipping activity – that noise that kills, maims, strands, pulps organs pulps organs and causes distressed cuttlefish to change colour too quickly. Self-deafened by our protective gear, we could still make out pale echoes of marine craft travelling through the Spencer Gulf to our location. These are sounds that our neighbouring non-human animals do not have the choice to not-hear, under-hear or un-hear. If I, with my land-ears stopped with putty and shrouded in face-squeezing neoprene, can make out the exclamations of my friend in the water, then how are the southern right whales, with their sensitive cetacean sonar, supposed to cope with Equinor’s 24/7 exploratory explosions directly to our south in the Great Australian Bight? What do we need to hear not just these sounds but also their contexts, the economic, political, military structures that make it so hard for us to unmute? Back in our airborne conversations, in the rec room, dorms, kitchen and by the fireside and back down on the stony shore, questions like these were surfacing.

If we call wild living “things” “reserves” or “marine resources”, we are objectifying them, making them into commodities. If we say “life” or “living ocean”, we may feel its will to live”. — Cecilia Vicuna

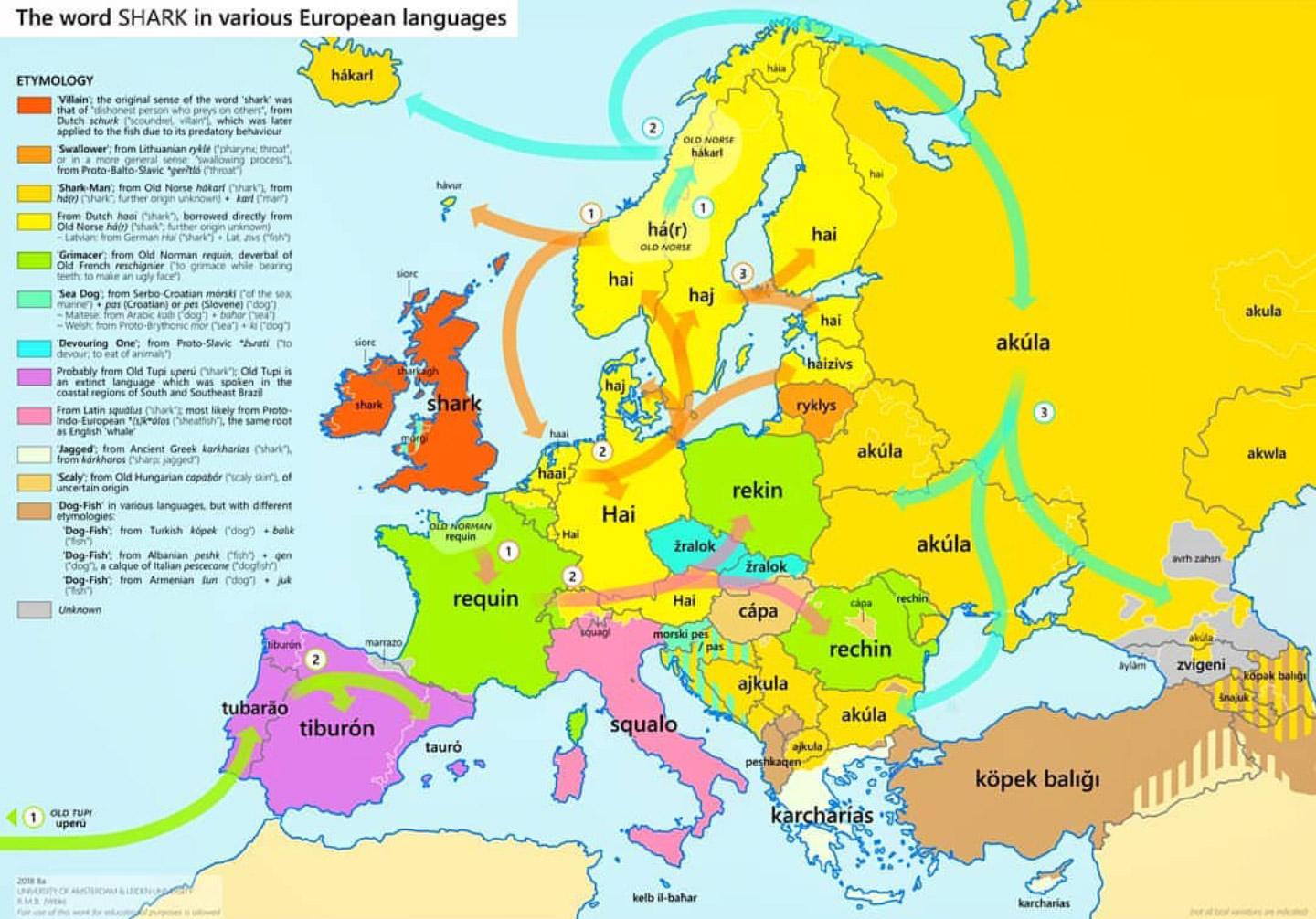

There was one other notable silencing on our Artist Camp. In the van on the first day - before we’d even dipped a fin in the water - the s-word had come up. You know, those really big fish. With the sharp teeth. Ssshh! We don’t say that word! Say whatever else you want. Say ‘sea dogs’. Men in Grey. Noahs. GWs. Big fellas. Say, ‘we’re gonna need a bigger boat’, if you must. Just don’t say the actual word. This is not a rational thing, this is a cultural thing: For a very long time now, humans have known not to say the name of the beast out loud, because to do so is to call it forth. (“Shitty fishing”, Norwegians say, but as Randy Nygard says, “what we mean is good luck fishing. But it is not wise to say that out loud. From older times, it might be that what you want to happen does not happen if you put it into words”). And as Liquid Architecture friend and scholar of sound Eric Bunger has told us, the role that animal names play, in the linguistic behaviour of humans, is often to move in and out of language. This was a word that we kept out of our Artist Camp language, a salt-dog taboo honoured as we settled on Cameron’s suggestion of ‘angry dolphins’.

Buoyed By Conversation

So there were some moments of silence, there was consensual silencing, and there was a reflection on what it means to be about to selectively silence ourselves and selectively (un)hear. But in general, of course, it was a very non-silent trip. Over a dozen experimental artists gathered in a regional location to witness the mysterious mating rituals of psychedelic cuttlefish was never realistically, going to be a monastic vibe. From morning until the wee hours - whenever we weren’t sleeping, basically - the nineteenth-century Point Lowly lighthouse cottage hummed with the buzz of artists in the wild. Around our two firepits, in the well-spec’d rec room transformed by Stephanie’s sensitive ambience engineering and processed by David and Joyce’s live sounds, on perchable shore-rocks and under the soft orange sweeping strobe of the lighthouse, new friendships were minted, and old ones levelled up. We picked up where we left off on the road trip, conversing and converging in media res, having already begun some months earlier with introductions, a cuttlefish-themed reading and learning event, and the formalising step of a group chat.

The Camp itself was built on conversations. We spent an impatient year of excited planning, reconnecting with the locals, like fisherman-raconteur ‘Fewie’ (whom we first met on 2018’s self-organised, pre-Artist Camp reconnaissance trip), and forging new friendships. One of those new friends, Adelaide University linguist Professor Ghil’ad Zuckermann was kind enough to facilitate mutual introductions between us and the Traditional Owners of the areas now known as Whyalla and Point Lowly, the Barngarla people, with whom he has been working for many years. Earlier in the year, Ghil’ad explained to us about the major project of reawakening of the sleeping Barngarla language, the formation of the

Barngarla Language Advisory Committee and the strong role of artists in the language revival project, which has recently resulted in the first

Barngarla languages alphabet and picture book and introduced us to elders, artists and teachers. Words cannot describe how thrilled we were, and remain, that our Artist Camp, a month before NAIDOC Week in the Year of Languages, could be, in small part, a celebration of the propagation of this sound throughout its land and beyond.

As summer turned to autumn, our dialogues grew and ripened, and the plan for a welcome from the Barngarla people blossomed into an artist-to-artist meeting and Barngarla language lesson for our artists. After months of talking long-distance, we finally met with Ghil’ad, gratefully receiving his compendious wisdom in conversations, publications and linguistic deconstructions his Adelaide Uni research-den, and continuing over lunch downtown. Fluidly free-wheeling, we met in the shared love of language as a political, aesthetic and practical force in our world. (Thank-you, Ghil’ad, for everything - including the gift of ikigai’, the ‘preoccupation’ contribution to Libby Harward’s Already Occupied project, for sharing the Hebrew pop-hit Libby with us, and for making the introductions that connected us with the Barngarla people).

We were honoured when our dialogues joined up in our meeting, on the first morning of the Artist Camp, with the Barngarla people in nearby Port Augusta, who shared stories of their Culture and connection to their Country, its land and waters. We were humbled by the Barngarla Traditional Owner Jason Ryan Dare’s strong and gracious welcome, which allowed us to hear Barngarla spoken for the first time. We listened to his gentle explanations of the ways of their language, the constellation of consonants that elide differences between some sounds and in some cases create new ones. Our tongues had some trouble getting around “yardlooloo” (cuttlefish), but we were nonetheless incredibly “warna moondalyidi” (glad, merry, uplifted) by Jason’s welcoming and wise words.

In their new Cultural Centre in Port Lincoln, Barngarla artists shared with us their paintings bringing together desert dot styles with modern references, and traditional objects decorated with symbolic meaning and personal aesthetics. Jeanne Miller is a Barngarla artist who brings contemporary thinking to traditional painting, and her artistic expression was very strong and distinctive for our artists, who learned about the decisions behind her choices in a series of artworks reflecting Jeanne’s thoughts and experiences. We heard about works by other artists, including Jason’s epic work about family and football, and were humbled by the artists’ decision to share with us some of the process, materials and stories informing their work, without which we would have a much less meaningful experience. And we deeply appreciated, over the course of that morning together, the sharing of images of special animals, stories from memories - first-hand and much older - and everywhere the presence of the country itself, in colours of rust and blood and fire, in curving salt-lake shapes and the metallic veins chasing each other down the side of Jeanne bawooroo (water carrier), like the ancient watercourses crossing the plains of Barngarla Country.

Like other Indigenous Nations, the Barngarla have to fight to be recognised as Traditional Owners of their traditional lands, which span from Port Augusta to Whyalla to Port Lincoln. As elder Linda Dare explained, theirs is a continuing fight for sovereignty, and also for the right to protect their land from the incessant attempts to locate our nation’s prime nuclear waste dump there. The Barngarla were among the stolen generation, and their language was a critical and unforgivable theft. It was an honour to hear their pride in speaking their language again, and we are grateful and excited for the opportunity to be their students, and their friends. We hope to return again to visit them and perhaps make some art together in the Barngarla Cultural Centre.

Language of Bodies

Back in the water, we blurted “two!” and sought our cuttlefish protagonists. It soon became obvious that it was going to be harder to find them than last year. We were early in the season; according to the dive shop there had been “some” seen but not many; the wind was getting up; and the current at Stoney Point wasn’t kind. Not a wild combination for us.

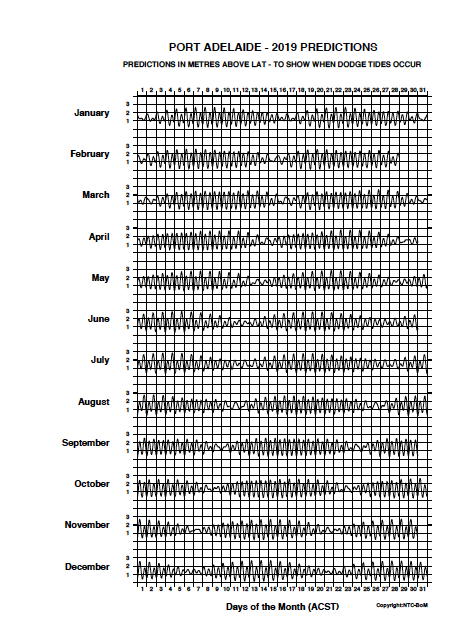

Apparently the locals and marine experts prefer to go out on the dodge tide the uniquely South Australian term for a super low neap tide, when the difference between high and low water is least (Another new language to learn, the dialogue between the powerful bodies of moon and ocean). We weren’t on a dodge tide, but our halting attempts to speak ocean, in prior consultation with almanacs and local advisors, meant that the camp’s date did fall over the period in which the moon became new, in early June, filled to first quarter. We’d tried to time things for the early part of the aggregation, when water temps were just low enough to promote both cuttlefish romance and human survival. Conditions which meant - theoretically - maximum chances of artist-cuttlefish encounter.

Nevertheless, we had a moment of wondering whether we might be hosting a concentrated gathering our nation’s most interesting artists on a remote peninsula five hours’ drive from Adelaide for what was about to be a cephalopod no-show. Doubts crept in, like the trickles of water worming their way between the wetsuit and warm land-body, and to deal with both we struck out further at sea.

Swimming in a full steamer, gloves, boots and flippers isn’t elegant or graceful. The crazy amount of buoyancy you get from the multiple puffy layers, the snorkel-huffing and weirdly abbreviated stroke give the wetsuited being an altered mind-body feedback dynamic. People talk about wetsuit swimming as being like ‘running in a dream’. So, dream-running together, we pushed further north, the mysteriously-long Santos jetty to our south and Black Point to the north, as the questions bubbled up.

These creatures have been gathering for who knows how long, but their numbers have been volatile - what if their situation was worse than we knew? So little is known about their lives beyond the time in which they come here to become multiple - what if they found another cephalorgy spot this year? What if they do come here, but later - after we leave? What if we humans have really done it this time?, the environment is actually cooked, and they are actually all just gone? And what does ‘some’ mean in the context of the language of a dive shop, anyway?

But then, maybe 50m north, suspended above the rocky shelves, our first cuttlefish appeared. That cold trickle magically transformed into a loving little bodywarming pocket of sweet insulation, as, in a flash, we were reminded of why we were there. Beneath us appeared a small group of maybe five cuttlefish on a sandy ledge, their little bodies pulsing with ever-changing rainbows.

Learning to read cuttlefish is a process. First you have to learn how to speak ocean, the language of tides and highs and lows and neaps and dodges and currents and knots (To do this, you pretty much have to speak basic moon too). Then you’ve got snorkelling, which, in addition to new breathing techniques, has the mask factor, requiring the acquisition of suction skills to make that sudden magical visual shift from salt-stung human blur to crystalline sea-creature clarity.

Once you can see, then you have to find them. You try to train your eyes for the giant cuttlefish form - a gliding shield shape, the size of a small dog - but unfortunately, since this is Stoney Point, SA, this is also the shape of most of the rocks around you (the right shape, it seems, to provide breeding and hatching grounds for giant Sepia apama for the decades of known, if unstable, cuttlefish aggregation at the site).

It was often only when rocks moved that we realised they were not in fact rocks that we had been hovering over, but rather cuttlefish who were imitating rocks, with their incredibly articulate skin capable of adopting not just environmental colour and pattern, but also texture. As we passed overhead, fronds became tentacles as entire seaweed societies disbanded, transforming back into mate-seeking molluscs. The shape search had to be extended to include anything that could be a rock or seaweed - which was everywhere that wasn’t water – so we focused on seeking out motion. Listening for cuttlefish became a mobile adventure with a mobile quarry - a very fluid situation, perhaps appropriate for a project co-imagined between Liquid Architecture and Forum of Sensory Motion.

Gradually, perception sharpened. It is likely also that they grew accustomed to, or tired of us, and stopped camouflaging - and it became possible for us to spend time with these animals, witnessing their interactions and also sensing of their presence in stillness and near-silence. (Listening with our eyes). Together we’d all read philosopher Peter Godfrey-Smith’s eloquent chapter, ‘Making Colours’, in Other Minds, and the author’s central question posed in that work – how might it feel to be a cuttlefish? – echoed through our minds as we finally encountered these other intelligences. We had wondered about Godfrey-Smith’s appeal to music as an explanatory framework for the creatures’ cycling colours and brilliant displays - Isn’t this just the ultimate expression of anthropocentrism - the attempt to capture and express the wonder of unknown through terms reassuringly familiar to humans? Why a symphony when there are so many other forms of marshalled sound a cuttlefish display could be productively compared to; what about their music? If thinking concerning the animal, as Derrida suggests, derives from poetry, could not also listening?

Here, in the water, there was definitely a pattern to the patterns, a reason why the cuttlefish changed in the different ways they did. After the fake-rock period, we knew the rainbow sea puppies were good at activating stealth mode. In addition to camouflage, we learned, as Peter Godfrey-Smith also noted, how cuttlefish who are chasing each other away seem to flash in distinctively fearsome messages, orange-red with fire-trails travelling down their bodies, with the arms held up high like horns. In conversation, we discussed the red signals. Was this aposematism – the use of intense colours in nature to signal toxicity? Should we take these examples to mean that red is some sort of universal language of danger across our planet on land and below? Possibly - but then brilliant reds and oranges, in this blue-tinted underwater world, were going to be the best colours anyway for that job of getting attention. But hang on; is it really blue-tinted or is that just how human optics - in body and in camera - read the scene? Is it really ‘blue’, or should we say ‘blue to human eyes’? (Trying to think like a cuttlefish). But then, we argued, aren’t they colourblind - in which case, how do they see each other’s red war-cries? (We are listening; we just don’t know how to understand what you are saying).

We picked up some other cuttlefish vocabulary in the water. Burgundy resting states with rhythmic ultraviolet pips like a waiting cursor. Half-seaweed, half-kaleidoscope forms of the location-shifting, the undecided, the unsingular. Rolling floral articulations of offer. The flashing silver no-thanks stripe reply of the uninterested. Glowing face-to-face entanglements climaxing with shimmering shockwaves of body-to-body pattern (and, erm, sperm packet) passing. The longer we spent with the cuttlefish, the more they seemed to be saying; or rather, the more we became aware they were saying things, things we were only beginning to intuit. We say intuit, because of course we are not scientists, and rather than study them per se, we kept our distance, respecting their space; trying to be with them, to be present quietly and attend and somehow understand them, in Cecilia Vicuna’s sense of feeling their will to live. We say intuit because with communion, with attunement, with feeling, with our attempt at listening bodily to the cuttlefish, their language did come to make a kind of sense to us, if only in the way that things make sense in a dream, or in poetry.

Double Taboo/Ask an Artist

The annual cuttlefish aggregation takes place in a land of complex overlapping stories. It is the traditional land of the Barngarla people who have connection to it stretching back to time out of mind. Whyalla, the nearest town to Point Lowly, is a town that was built by BHP at the start of the 20th century to serve its mining operations; its steelworks, as we saw on our guided tour, remain the lifeblood of the town.

In nearby Cultana, military training exercises take place on grounds that include the former Baxter detention centre. Point Bonython hosts the Santos oil and gas refinery, whose jetty juts into the ocean and whose towers burn with periodic eruptions of flaming off-gas. The cuttlefish gather at Stoney Point, whose accommodation options include quarters set aside by BHP for their workers, is the historic lighthouse-keeper’s cottage in which we now stay for our Artist Camp. Our aggregation brought a cadre of professional shapeshifters to witness a threatened natural wonder, and experiment with different kinds of embodied, ultra-present listening in the hope of creating new logics of exchange, or the principles that might make them possible. In silence and in din, in the water and on the land, in the periodic flashes of the lighthouse beam, there was no resolution, no completion, only oscillation between multiple coexisting truths.

To commit oneself to such a principle is almost an act of faith, since how can one have certain knowledge of such matters? It might possibly turn out that such a world is not possible. But one could also make the argument that it’s this very unavailability of absolute knowledge which makes a commitment to optimism a moral imperative: Since one cannot know a radically better world is not possible, are we not betraying everyone by insisting on continuing to justify, and reproduce, the mess we have today? And anyway, even if we’re wrong, we might well get a lot closer. —David Graeber

Artists especially understand that there is a need to quieten the mind, particularly after stimulating conversations, and a value in allowing the senses to take over. Floating above energies more luminous and less knowable than our own taught us about communication and non-communication; about silences we preserve because we have to, the silences we preserve because we want to, and the challenge of knowing the difference.

Acknowledgements

Our Artist Camp took place on the traditional land of the Barngarla People. We acknowledge the Barngarla People as the traditional custodians and the cultural authority of their ancestral land.

We acknowledge the deep feelings of attachment and the maintained relationship of the Barngarla people to the land and the sea.

We acknowledge all Barngarla elders; past, present and future, and respect that their spiritual and cultural practices are important to the living Barngarla People today.

Thanks

We give deepest thanks to Linda Dare, Jeanne Atkinson, Steven Atkinson, Jenna Richards.

Big thanks also to Chris “Fewie” Fewster, his mate and Swannee at Whyalla Dive Centre.

Professor Ghil’ad Zuckermann’s generosity, advice, interest and time made many things possible on this trip and we thank him for all of them.

Karolin Tampere’s project The Wild Living Marine Resources Belong to Society as a Whole was a source of inspiration for this project.

Cecelia Vicuna’s words continue to inspire and resonate within us.

Tessa Laird provided inspiration and spirited discussion of Other Minds, and we are grateful for her for sharing and encourage cephalopod enthusiasm.

Jo Driessens’ leadership of Stradbroke Island Indigenous Artists’ Camp was the inspiration for this form of artist camp.

The team at Liquid Architecture.

Forum of Sensory Motion.

Finally, we would like to give thanks to the artists who joined us on this project, and to each other.

— Danni Zuvela and Lichen Kelp (June 2019)

References

Barngarlalidhi Manoo, “Speaking Barngarla Together”, Barngarla Alphabet & Picture Book, Introduction to the Barngarla Language, Written by Linguistics Professor Ghil’ad Zuckermann with the Barngarla People of Port Lincoln Port Augusta & Whyalla, Barngarla Language Advisory Committee.

Eric Bunger, The Elephant who was a Rhinoceros

Graeber, David. Fragments of an Anarchist Anthropology. Cambridge, England: Prickly Paradigm Press, 2004.