Cultivating Communities:

Listening as Counter to the Colonial Gaze

Glenda Nalder, Ngugi, Quandamooka

(November 3, 2018)

Ngugi Bajara (Ngugi Footsteps) is an ongoing creative collaboration between writer Dr. Glenda Harward-Nalder and Artist Libby Harward. Glenda and Libby are descendants of Junobin of Mulgumpin (Moreton Island) in the Quandamooka (Moreton Bay), through her daughter Rose Gonzales-Campbell. Granny Rosey’s Ngugi tribal name, Widjum-baragun, relates her to the Black Dolphin.

We pay our respects to the Miginjin (First Peoples of the Lower Brisbane River Area), and their Elders, past and present.

The invitation by Liquid Architecture to participate in “Why listen to plants?”, curated by Dr. Danni Zuvela of Liquid Architecture, provided an opportunity to share an aspect of our work with other First Nations peoples in a global context.

Botanical and other concepts

First Nation Peoples listen to plants and plants listen to us. Ours is a reciprocal relationship. In First Nation ways of relating, the people belong to the land in community with all living things. In our language, places are named for the plants or foods that grow there, e.g., gulburbin (place of the dugong grass) or, ngarangarawayi (long winding creek where swamp heather grows abundantly) or for their special geographical features.

When the first colonial botanical garden in Miginjin (our language name for Brisbane) was constructed, the fertile land on that spike in the northern bank of the river near the first house of government was host to mangrove communities, including the marine life that nourished us.

A botanical garden is an alien concept in First Nations culture. In our culture, we belong to country, where all things are interrelated, and nature and culture co-evolve. This is in contrast to the relationship between people and plants in Western civilisation, whereby living entities are divided into human and non- human, and the human has dominion over the non-human ‘other’. This is most evident in language through our divergent ‘naming’ conventions for plants and places. In the West, the name of the individual human ‘discoverer’ - as the objective, external observer and recorder - is privileged.

The survival of Ngugi culture

Within the Moreton Bay area (the Quandamooka), the coastlines and islands of which can be seen from this mountain place we call Kuta (where honey is found) the highest point of Miginjin. From time immemorial, our people paddled their canoes across the bay and up the river to meet other tribes on the hills surrounding Miginjin for cultural and resource exchanges and a variety of recreational activities, including ganjiyil (corroborees) and staged spear fights that the new arrivals – British convicts and free settlers – found both frightening and entertaining.

From the 1840s the Ngugi people were participating in the economy of the new settlements of Moreton Bay, selling fish, oysters, and dugong oil, piloting boats through the dangerous waters of the bay. Visitation to our Island campsites by British subjects on various missions was a regular occurrence, and their subsequent reports on their observations entertained a readership in their home country. Our enterprising dancers soon learned to demand payment for their performances of new comedic works based on their observations of the strange behaviour of the new arrivals that they created for this purpose.

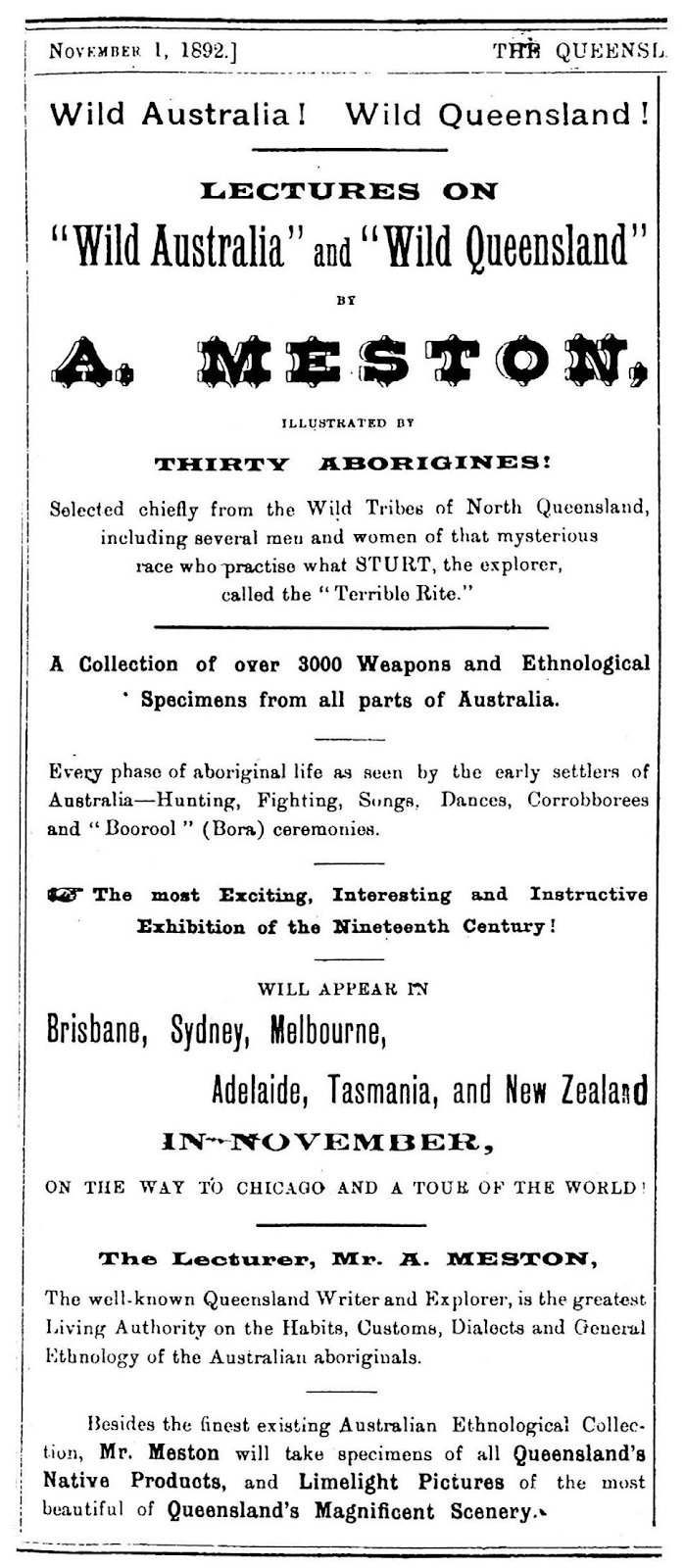

However by the 1890s interventions by missionaries and public servants whose role was to ‘civilise’, control and assimilate our people into white society using the instruments of British Law caused a shift in relations. Archibald Meston, the ‘Protector’ of Aborigines, initiated proceedings leading to the passing of The Aboriginals Protection and Restriction of the Sale of Opium Act, 1897, which gave control to the state and church authorities over people who were deemed to be:

an aboriginal inhabitant of Queensland; or a half-caste who, otherwise than as wife, husband or child, who habitually lives or associates with aboriginals.

[Subsequent legislation, The Queensland Aborigines Preservation and Protection Act and the Torres Strait Islanders Act 1939:

maintained the reserve, mission, and state depot system and legalised the removal of our people from our homelands to distant reserves, mission stations and government stations outside of townships; the removal of our children by force (stolen generations); restrictions on our movements; the destruction of our language and kinship groups; the disruption of cultural and social relations; compulsion to work for low wages; the withholding of wages without consent (stolen wages); random seizure of our property; exclusion from voting in elections of government; and curtailment of access to processes of justice that were available to the rest of the community.]

While in his role as Protector, Meston established himself as the authority on the First Peoples, obsessively recording “a dying culture” and engineering his own version, which he demonstrated in in public parades and processions, and showman-style in theatres, using crews from the missions and reserves that he created.

Mount Coot-tha Botanical Gardens

The new civic botanical gardens, constructed in the 1970s on a tract of land in a valley at the base of Mount Coot-tha (kuta) sit on what today is the edge of Brisbane Forest Park. This garden was constructed to replace the original Botanic Gardens at Gardens Point, which was frequently reclaimed by Nature through regular flooding of this wetland, and also shrinking in size due to the encroaching built environment.

This new site was established within the vegetation community of the open dry eucalypt forest comprising the Spotted Gum (Corymbia varigata), the Grey Gum (Eucalyptus propinqua), the Forest Red Gum (Eucalyptus tereticornis) and the Narrow-Leafed Ironbark (Eucalyptus crebra) sits The Dome (a hothouse for exotic plants).

On ‘Intertropical Appearance’: What can we learn from listening to the plants in The Tropical Dome hothouse?

The Tropical Dome is a present-day manifestation of the Western scientific tradition practised throughout the British Empire since “The Enlightenment” (the emergence of the Europeans from their perceived dark, ignorant past) and the role of The Surveyor, The Naturalist, The Botanist and The Artist in this journey.

The new community of exotic tropical plants in The Tropical Dome hot-house tell us an originary story of possession of country and dominion over it that began with the arrival on our shores of James Cook, a cartographer, mathematician and navigator, his botanist, Joseph Banks, and Swedish naturalist, Dr. Daniel Solander, on the shores of Terra Australis Incognita (unknown southern land), in the year 1770. The scientific method was applied to the endeavours of these seafaring adventurers. On board Cook’s ship, The Endeavour, and the ships undertaking subsequent voyages, were surveyors, scientists and artists. Their role was to map, claim, collect and record, for the British Crown, the lands and waters, and samples of species of animals and plants that were indigenous to the “new worlds” that their sailing ships could now reach. During the Endeavour’s voyage, Banks and Solander collected nearly 30,000 dried specimens, eventually leading to the description of 110 new genera and 1300 new species, which was said to have increased the known flora of the world by 25 per cent.

To facilitate their allotted tasks, the botanists, naturalists and artists applied the accessible taxonomy created by Swedish natural geographer, Carl Linnaeus (1707-1778) – Solander’s university lecturer. From various sources, Linnaeus created one Global Classificatory Tree encompassing “all life on earth, and divided into five levels of generality: class, order, genus, species and variety” (Koerner, 1998). Each specimen was removed from its community, duly documented, and archived for future study and incorporation into the realm of Western knowledges about the world. Some specimens were living specimens, some were in the form of seeds that could be propagated and grown in hothouses, designed to simulate the climatic conditions of the exotic specimens. Linneas’ taxonomy is still used by botanists today.

The notorious Archibald Meston (referred to earlier) published a book titled “The Geographic History of Queensland” in 1895, which he dedicated to “the people of Queensland”. Among the topics covered in its chapters was one dedicated to the Flora of Queensland (pp. 98-102), in which Meston reviewed those who had collected “since Dr. Solander visited our coast with Captain Cook, in 1770, and collected at Bustard Bay, Broadsound, Cape Grafton, Endeavour River, and Lizard Island.” Meston’s “brief outline of Queensland hunters in Flora’s realm from Captain Cook to the present time” (1889) numbered 22, and included himself, and notably, “Mr. Walter Hill, long the curator of Brisbane Botanic Gardens (from 1855)” who “collected with Dalrymple’s north coast expedition in 1874, and went on to the north spur of the Bellenden-Ker Range, the scrub ironwood (Myrtus Hilli) bear(ing) his name.”

Also included in Meston’s list was Naturalist John MacGillivray, who sailed on the voyage HMS Rattlesnake, which was under orders to survey the inner route along the Great Barrier Reef and to chart the southern coast of New Guinea in 1848. Young marine artist, Oswald Brierly, accompanied MacGillivray on this voyage. An album of his sketches was compiled by the ship’s commander, Naval Officer Owen Stanley, who was under orders to survey the inner route along the Great Barrier Reef and to chart the southern coast of New Guinea.

MacGillivray recorded in his “Narrative of the Voyage of HMS Rattlesnake” (1848) that they were at anchor off Mulgumpin for 16 days of observation:

1848: Cape York and Moreton Island: 10 : 38 : 23.4 : 6 : 10 49 10 E :—: Watering−place, North−west end of Island : 27 5 44 S :—:—.

Moreton Island, under the lee of which the Rattlesnake was at anchor, is 19 miles in length, and 4 1/2 in greatest breadth. It consists for the most part of series of sandhills, one of which, Mount Tempest, is said to be 910 feet in height; on the north−west portion a large tract of low ground, mostly swampy, with several lagoons and small streams. The soil is poor, and the grass usually coarse and sedge−like. All the timber is small, and consists of the usual Eucalypti, Banksiae, etc. with abundance of the cypress−pine (Callitris arenaria), a wood much prized for ornamental work. The appearance along the shores of the Pandanus or screw−pine, which now attains its southern limits, introduces a kind of intertropical appearance to the vegetation. Among the other plants are three, which merit notice from their efficacy in binding down the drift sand with their long trailing stems, an office performed in Britain by the bent grass (Arundo arenaria) here represented by another grass, Ischaemum rottboellioide: the others are a handsome pink−flowered convolvulus (Ipomoea maritima) one stem of which measured 15 yards in length, and Hibbertia volubilis, a plant with large yellow blossoms. (p. 114).

Many of these plants, listed by MacGillivray in the typical taxonomical European style, are in fact part of important plant communities and ancestral cultural practices on Mulgumpin (Moreton) and Minjerribah (Stradbroke) islands). Examples include the cypress-pine, which served important role in fire propagation (a slab of whose green bark was cut and used by the women to carry coals from a fire to a new location, since women did not make fire using firesticks); Wineem/Winnum (Pandanus, whose ripe orange fruit segments were roasted in the fire, the fibrous outer part scrapped away, and the inner seeds (kernels) removed and eaten, possessing a sweet nutty taste.); and Tharook (pink beach convolvulus, whose leaves were scorched over the fire until they blistered, then placed on the forehead for treatment of headache, and whose crushed leaves were also used to ease bluebottle and stonefish stings, though the sufferer of the latter, if stung by a stonefish when the tide is in, has to wait until the tide goes out and tide comes back in again before the pain eases) (Stephens and Sharp 2009, p. 4; p. 18; p. 3).

In addition to his botanical collection, MacGillivray also sought to collect specimens of marine animals, but had reservations about procuring

an undescribed porpoise … as the natives believed the most direful consequences would ensue from the destruction of one; and I considered the advantages resulting to science from the addition of a new species of Phocoena, would not have justified me in outraging their strongly expressed superstitious feelings on the subject. (p. 20).

The aesthetisation of nature as a means to preserve and protect plant communities

Early (19th Century) immigrant Artists unwittingly played a role in present day approaches to preservation of “heritage” vegetation communities in The Australian National Estate, (the politico-regulatory construct around heritage and place first advanced by the Whitlam Government in the mid-70s) through the integration of aesthetic values in preservation criteria, defined as follows:

Aesthetic value is the response derived from the experience of the environment or of particular cultural and natural attributes within it. This response can be either to the visual or to non-visual elements and can embrace emotional response, sense of place, sound, smell and any other factor having a strong impact on human thought, feelings and attitudes (quoted from Paraskevopoulos, 1993, p.79 in Lennon & Townsley, 1998, pp.1-2).

Thus evidence to support the inclusion of Queensland forests in The National Estate was drawn by authors Lennon & Townsley from representations found in art, poetry, literature, folk art, local identity imagery, folklore, mythology, etc. (‘works of art of forest places’) which were considered indicators that a particular site within forests was a “symbolic landmark” (op cit, introduction, unpaginated).

The authors saw their project as:

…one of discovery … what it has uncovered is testimony to the cultural and aesthetic value of our forests to successive generations, a value that is being rediscovered by a new generation of Queensland artists. Across artistic forms and genres it is apparent that there is an increasing desire of young artists to cite the specificity of place in their works: an indication of a renewed sense of connection to the landscape and forests in this region. (ibid)

Significant contemporary artists and historical figures inspired by forest places in the region under study ranged “from Judith Wright to Peter Carey to Janette Turner Hospital, from Conrad Martens to Vida Lahey to William Robinson”. A work of relevance to Quandamooka People included in the register was Arthur and Corinne Cantrill’s (1963) film The Native Trees of Stradbroke Island, which they made to record endangered native species, Casuarina Equisetifolia, Pandanus pedunculatus, and two others collected by, and subsequently named after, the Endeavour’s botanist, Joseph Banks (Banksia serrata and Banksia integrifolia). Their aim was to encourage the preservation of these species, which remained in small patches, where “‘development’ had not razed the bushland”.

That no contemporary artworks by Queensland First Nations people were included in the list was “a significant omission” noted by the authors:

The work of contemporary Indigenous visual artists such as Vincent Serico and Ron Hurley who live and work in this region require further research. One factor influencing this is the lack of time to appropriately consult with Indigenous artists and organisations as well as organisations servicing Indigenous artists in the South East Queensland region. Another is the lack of published catalogues about Indigenous aesthetic works. This is a significant omission and is discussed further in Section 4, Directions for Further Research. However, the Brief did not ask for Indigenous work to be included here as there are separate consultancies being undertaken by Indigenous people (ibid., p.9).

Contemporary Australian Indigenous Art relating to nature, place and Country

Today most public and many commercial art institutions hold and/or exhibit works by First Nations visual artists, writers, performers, playwrights and filmmakers. Almost without exception these works reference “Country” and aspects of our shared history since first contact with Europeans. An important work is of course the poetry of Oodgeroo (Kath Walker), which listens and responds to the Natural World of Minjerribah (Stradbroke Island) in the Quandamooka.

Contemporary Indigenous Art can be found among many genres of art practice - Public Art, Street Art, Environmental Art, Performance Art, Installation Art, and Sound Art.

Australian First Nations symbolic culture from time immemorial (on current Western scientific assessment, at least 60,000 years before the present), arises from and relates to Country. Contemporary versions of our symbolic culture entered the Western classification “Art” in the 1970s with the evolution of “dot” painting in the remote Northern Territory settlement of Papunya.

It is evident today that First Nations cultural practices have sustained through the development of forms of resistance to threats of extinction, and through creative adaptation to the prevailing natural and introduced conditions – i.e., the constructed environment of the colonisers, and their transplanted species, that deplete the natural world of indigenous plant communities

Site-specific speech in the Tropical Dome and beyond

Artist Libby Harward’s sound artwork in the Tropical Dome hothouse at Mt Coot-tha Botanic Gardens arises from and extends her practice of listening, calling out, and thinking whilst on Country. This work responds to the specificities of place with a cascading series of First Nations voices, each emanating from a different ‘exotic’ species on display in the dome. The spectator experiences an immersion in a syncretic field of plant voices speaking to multiple overlapping histories of colonisation and exoticism, from the West Indies to South America, South-East Asia and the Quandamooka. One could say that this work subverts the usual colonial visual regime, in which the exotic other is the object of the gaze, with a practice of considered sounding-and-listening that turns the plants (back) into speaking subjects, each saying, in their language, ‘why am I here?’. Our collaborative practice – Ngugi Bajara – (Ngugi Footsteps) continues the traditional cultural practice of walking in the footsteps of our Ancestors, and connecting back to our Ancestors through shared listening, calling out, and deep thought, or understanding.

References

- Brierly, O. (1848), Gum Trees near Sydney (sketch), in Stanley, O. Voyage of HMS Rattlesnake, Vol. 1. Downloaded from the series Painting the Pacific, in the Picture Gallery: Guide, State Library of New South Wales. Curator, Warwick Hirst. State Library of NSW, Sydney (2002). Retrieved from: http://archival.sl.nsw.gov.au/Details/archive/110320921

- Harward-Nalder, G. & M. Grenfell (2012), “Learning from the Quandamooka,” in Arthington, A.H. et al, A Place of Sandhills: Ecology, Hydrogeomorphology and Management of Queensland’s Dune Islands. Proceedings of the Royal Society of Queensland, Vol. 117, pp. 495-501.

- Koerner, L. ‘Carl Linnaeus in his time and place’ in Jardine, N. (ed.) (1996) Cultures of Natural History. Cambridge University Press, Cambridge, pp.145-6

- Lennon, J. & M. Townsley (1998), ‘Integration of data for national estate aesthetic values studies’. Queensland CRA/RFA Steering Committee. Queensland Government Department of Natural Resources, Brisbane & The Forests Taskforce, Department of Prime Minister and Cabinet, Canberra.

- MacGillivray, J. (1852), Narrative of the Voyage of HMS Rattlesnake, T.W Boon, London.

- Stephens, K.M. & D. Sharp (2009), The Flora of North Stradbroke Island. State of Queensland, Environmental Protection Agency, Brisbane.